Throughout 2020, I’m working with the North Lakes National Trust to on a socially engaged art project focusing on Crow Park in Keswick, as part of the Trust New Art programme. For more information please see the project page.

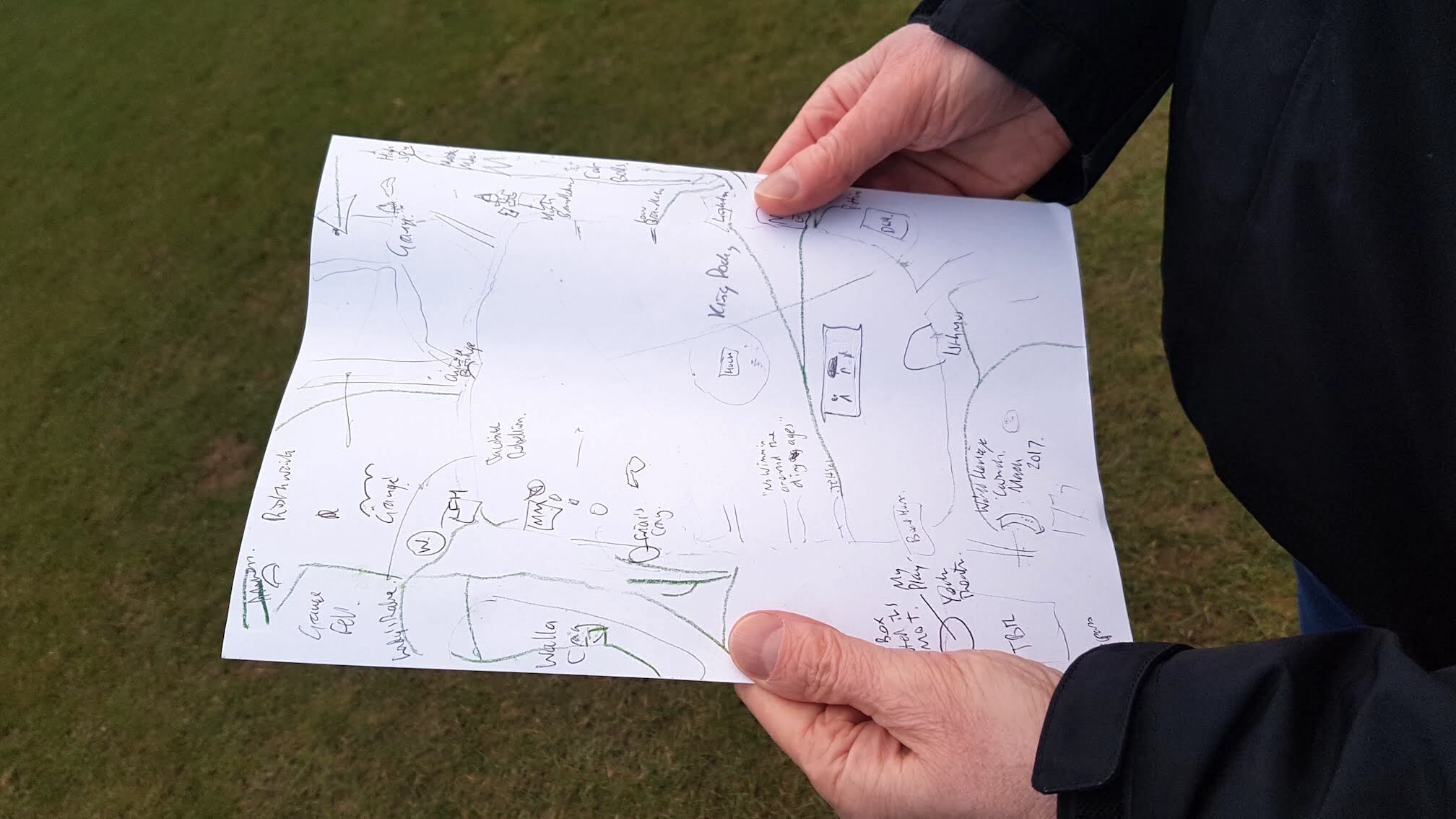

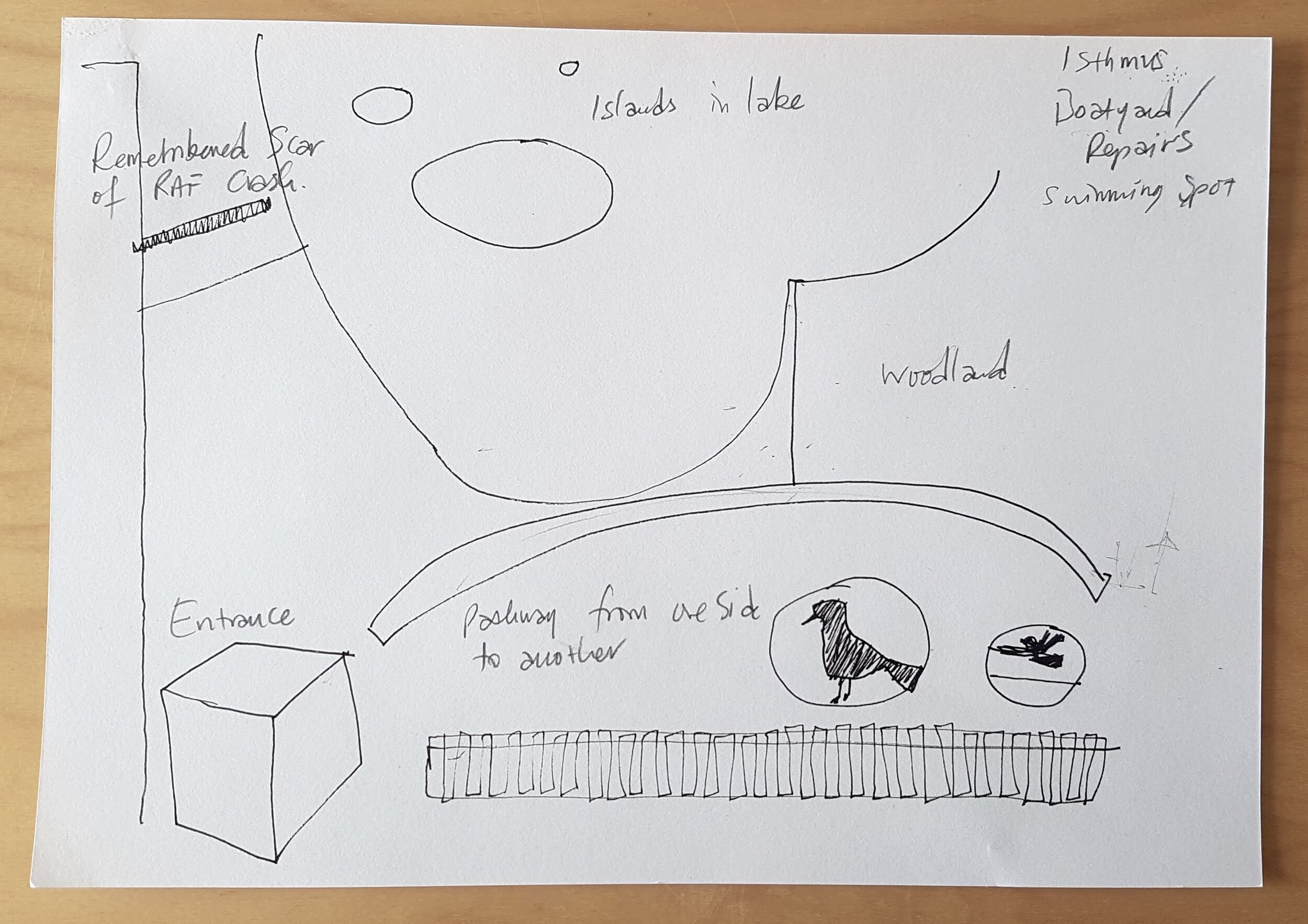

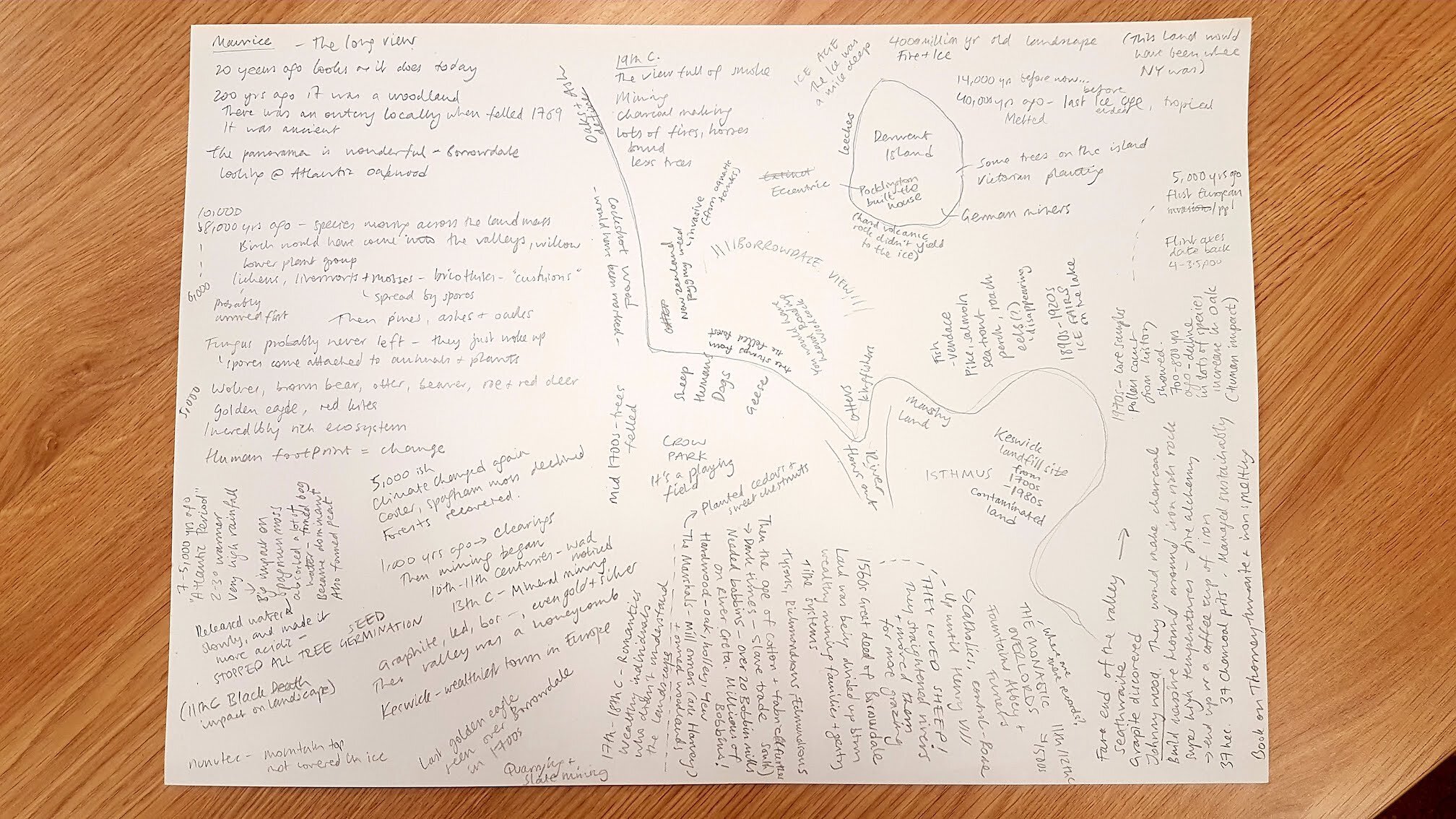

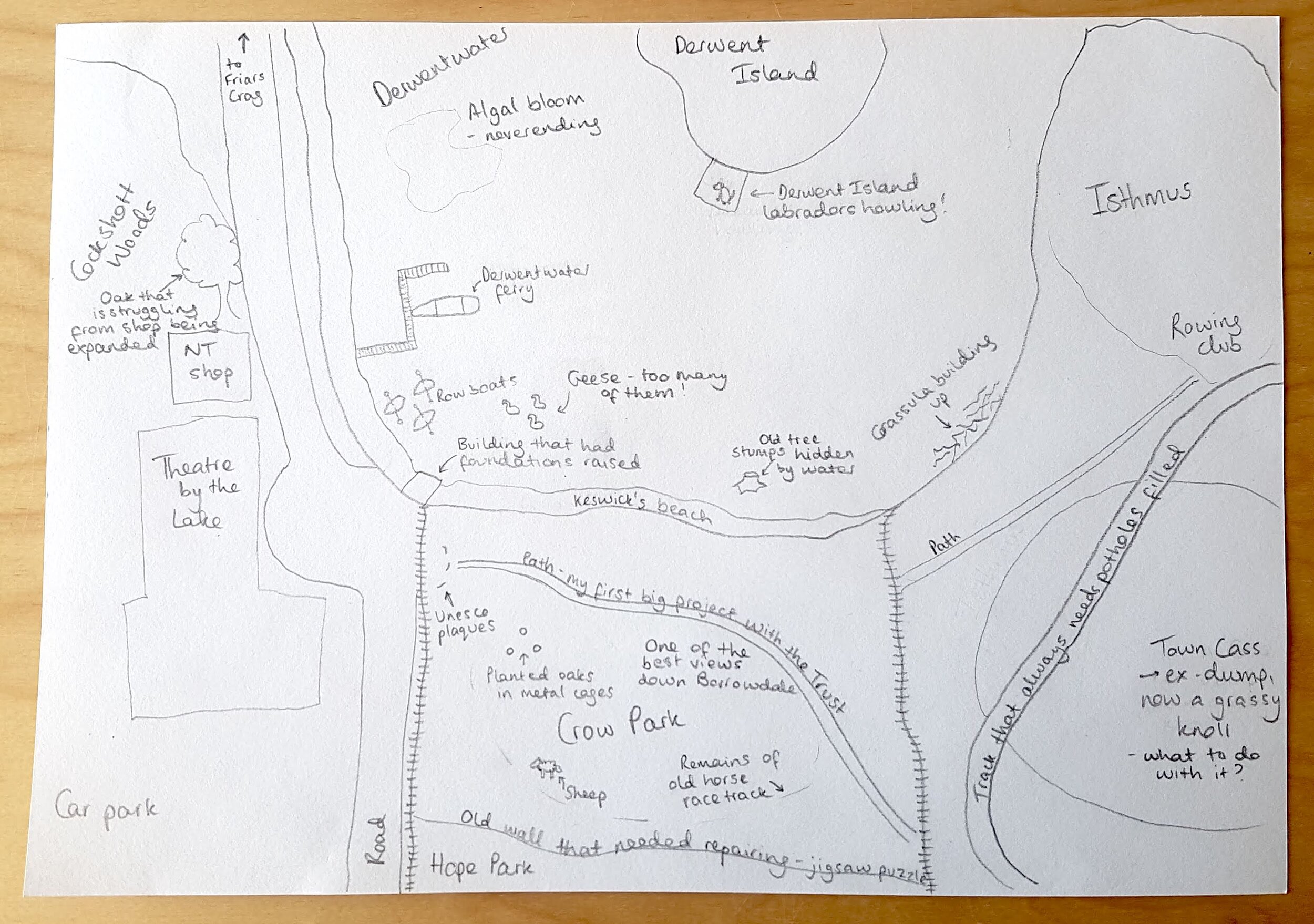

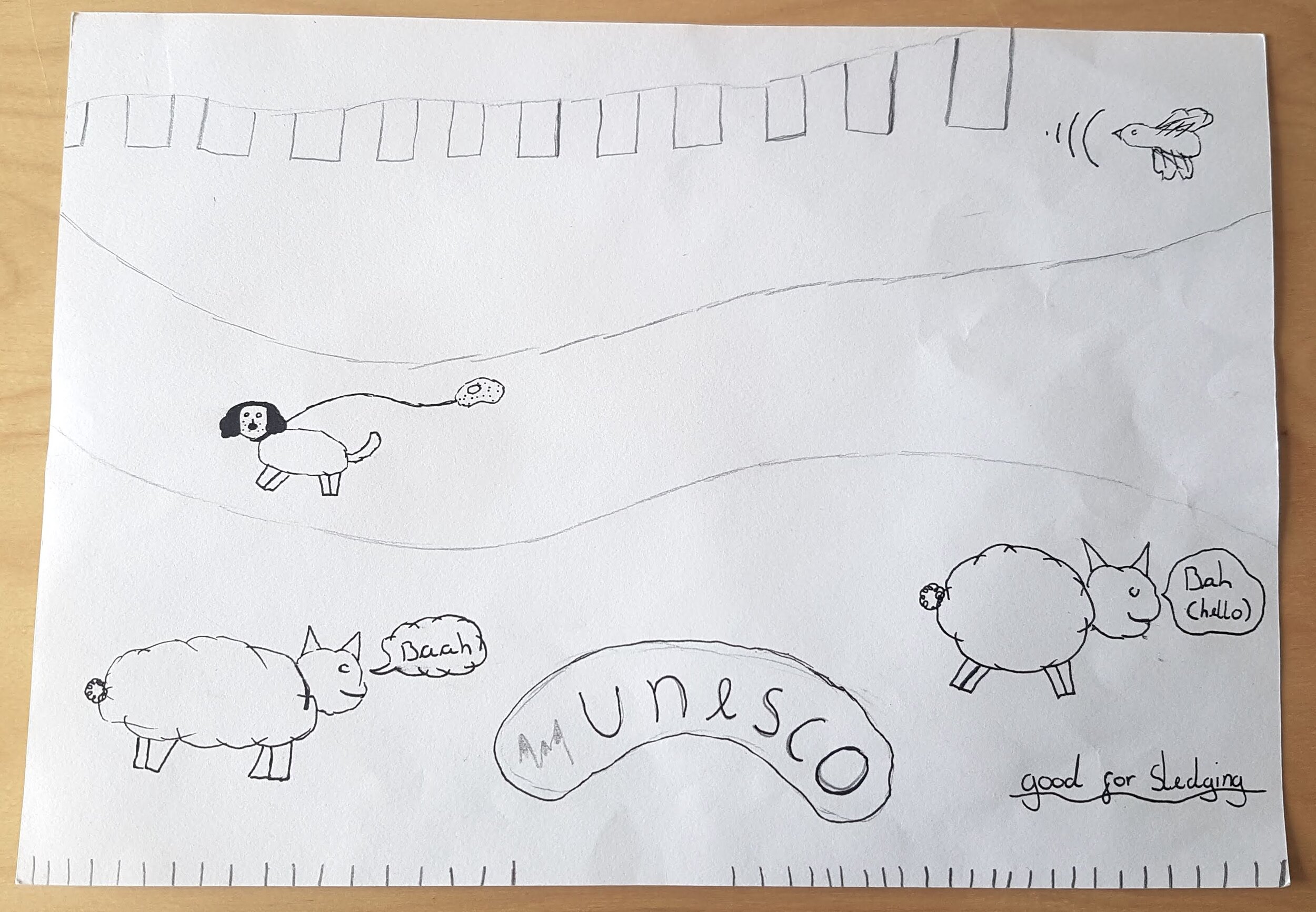

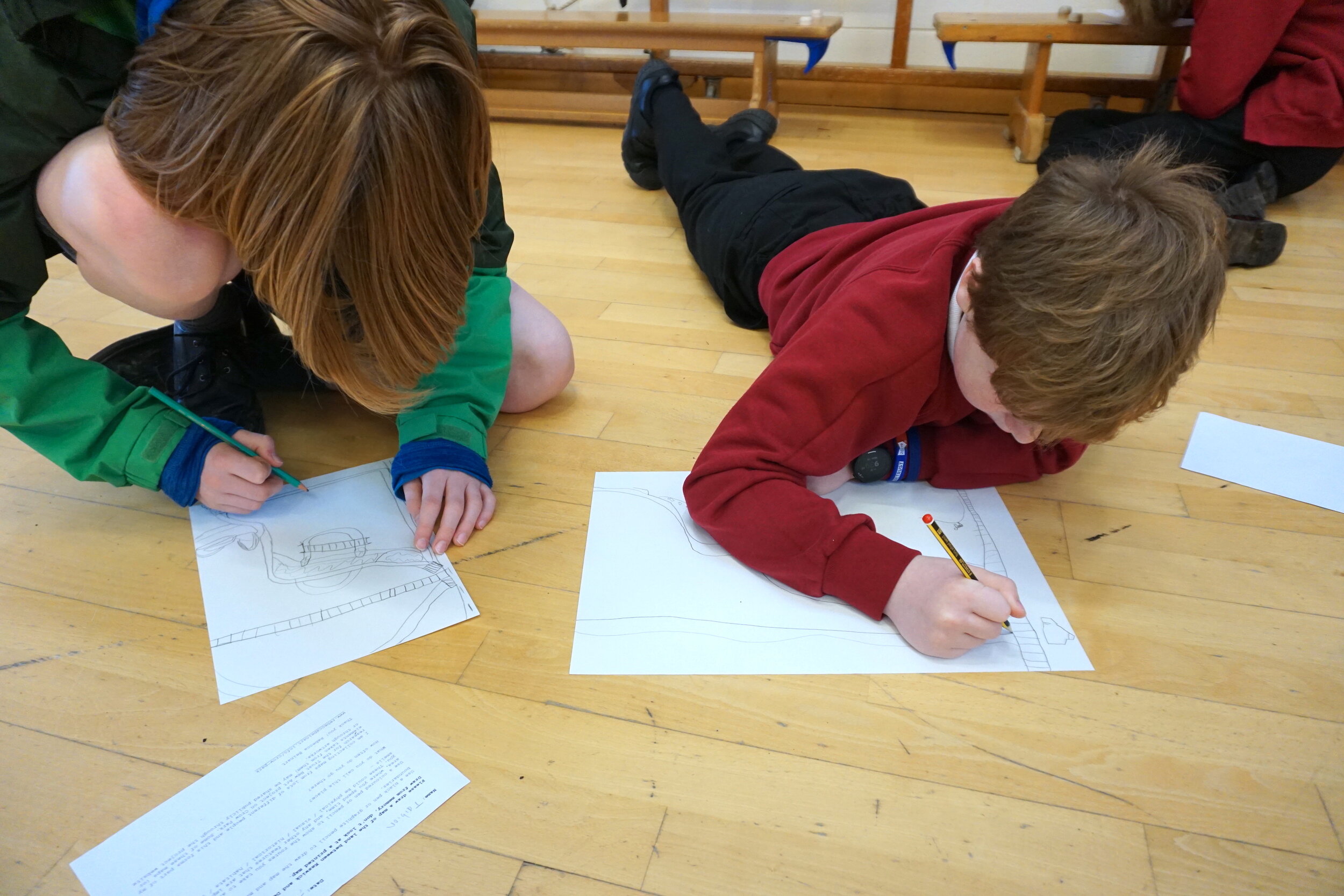

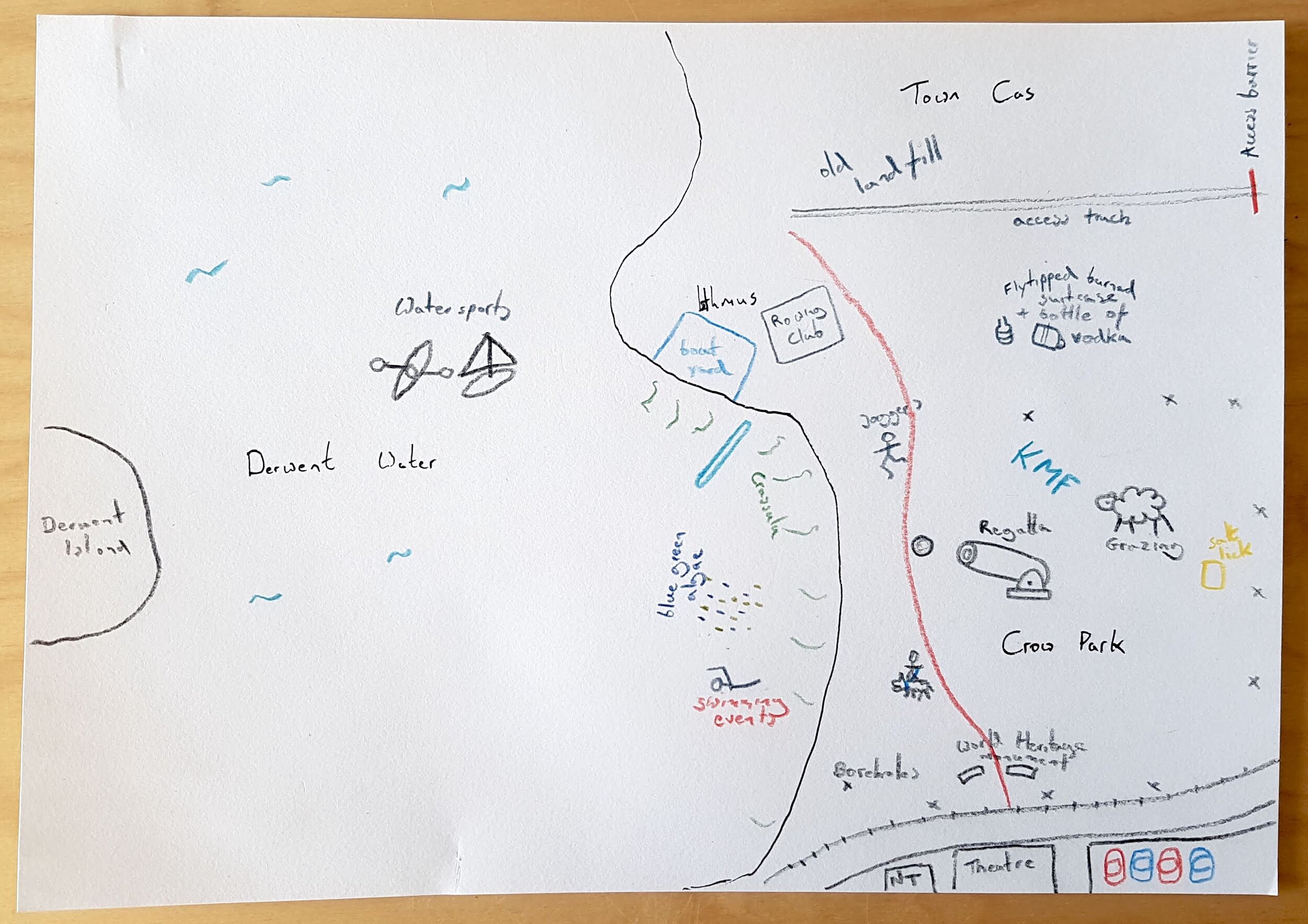

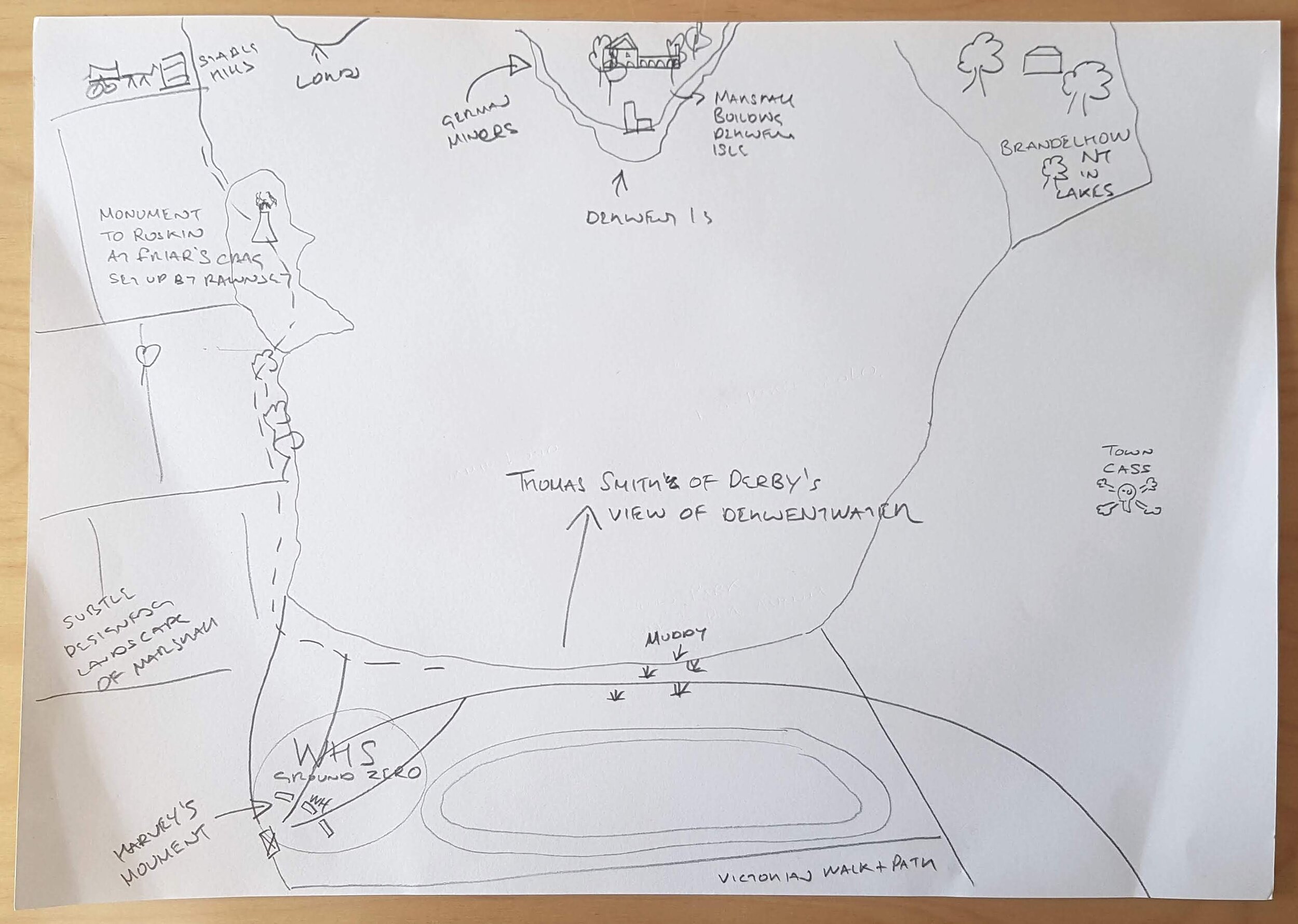

In my first few visits to Keswick, I invited everyone I talked to about Crow Park to draw me a map. The invitation was to draw from memory, to treat it as the back-of-an-envelope, to take me for a real or imagined walk around the site. Each map and conversation offered a different perspective on the place, and so far I've been lucky to speak to National Trust staff and volunteers, local residents, an archeologist, staff from Keswick Museum, a geology enthusiast, a group of children from St Herbert's School, and a town councillor. I'd love to hear from more people, if you'd like to draw a map, please follow this link.

I have gathered 23 maps so far, and along with the story-telling that accompanied them, they reveal a well-used and well-loved green space layered with memories and stories. A place deeply, richly, entwined in our understanding of landscape – from deep geological time to the ice age, to 11th century 'monastic overlords' introducing sheep farming, 15th century intensive mining industries, the Picturesque and Romantic movements culturally framing the Lake District, Crow Park as a 'Viewing Station', 19th century conservation movements, the founding of the National Trust, and the recent plaque on Crow Park marking UNESCO World Heritage status. But Crow Park is also an agricultural field, where a flock of Herdwick sheep periodically graze. And it is an everyday, municipal space – a place for recreation and relaxation. Keswickians walk their dogs there, have picnics, kids play games, tourists and locals alike marvel at the views, it's a place to catch a moment of peace in your lunch break. It's the way to Booths, or the way to the Theatre, depending which way you look at it. It's both ordinary and extraordinary. In future posts I'll be sharing some of these stories in more detail.

The many layers these maps reveal remind me of geographer Doreen Massey's description of place as ‘always unfinished and open’. Cartography is an ancient art and as well as becoming essential for navigation, maps have historically been tools to mark territory - pinning down imposed boundaries and confirming ownership. Colonial maps re-named places, often erasing the people and stories of the lands they depicted. But community mapping has been used by groups around the world as a way of telling multi-faceted versions of a place. Rebecca Solnit's Atlases project is a beautiful example of this approach to mapping shifting personal, political and imaginative terrains.

As I work with the maps, I've been compiling a list of names and phrases people use to describe this site:

Crow Park

The field

The park

The hill

Playing field

Municipal space

Grassy mound

An agricultural field

Keswick Lakeshore (I've always felt Keswick comes right to the Lake)

Keswick Foreshore

Derwent foreshore

Keswick's only beach

Rowing Club World

A through place

The way to Booths

That place next to the Theatre

The route to the Theatre

Home

A piece of parkland, a piece of urban green

A designed landscape

That big domed expanse of grass

A nothing space

A place where national debates about landscape are played out

The centre of a compass

World Heritage ground zero

The place I fell in love with this landscape

The view

Thanks to: Jessie Binns, Roy Henderson, Maurice Pankhurst, Jamie Lund, the North Lakes Ranger team, Dave Cryer, Livi Adu, Keswick Museum, St Herbert’s School and Sally Lansbury for the maps and conversations and everyone else who has contributed a map so far.